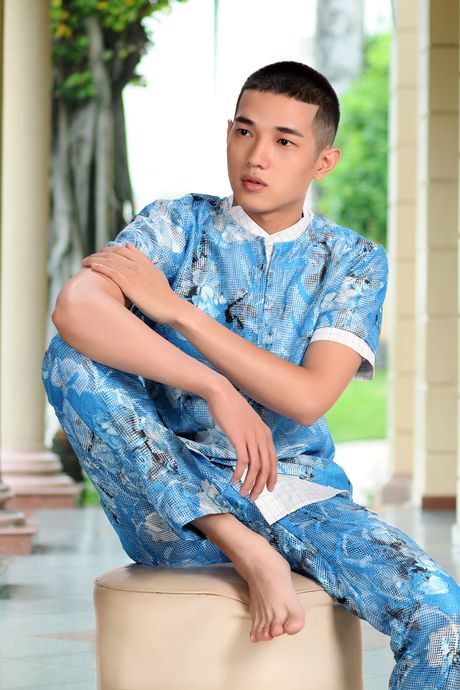

A model in CFGNY’s Fashion Max 2.

Photo: David Brandon Geeting

At the end of January, Japan Society was packed for an event it hadn’t staged since the 1970s: a runway show. Models decked out in pants with large dangling fringe; plastered in tops made of layered text; and wrapped in printed, close-fitting dresses strutted through the Junzō Yoshimura–designed building. Fashion Max 2 was the latest presentation from CFGNY (Concept Foreign Garments New York), a fashion collective whose New York solo debut is on view in “Refashioning” at the midtown institution.

But CFGNY’s members are hesitant to call themselves fashion designers. “I would describe CFGNY as artists who make clothes,” says Daniel Chew, one member of the four-person collective. Chew creates films with Micaela Durand, and Tin Nguyen has his own multimedia practice. But “we wanted to expand conversations we were having to other people, and we thought the easiest way to do that was through doing a fashion show, where we could invite a lot of strangers from online to partake in a project together,” recalls Chew. They founded CFGNY in 2016 with multimedia artists Kirsten Kilponen and Ten Izu joining in 2020. Together, they also produce videos, sculptures, installations, and performances.

From left: Kirsten Kilponen, Daniel Chew, Ten Izu, and Tin Nguyen of CFGNY.

Photo: Courtesy of Stefani Oh/Japan Society

Coming from different backgrounds, Chew says the collective is united in part by the feeling of “shared alienation” that comes with being Asian in America. “We describe CFGNY as being ‘vaguely Asian’ — and part of that definition is that we’re a bit undefinable,” says Chew. They have played with themes like mistaken identity and the nature of time in performances and installations across Europe and unearthed Chinese and American historical objects to be displayed alongside their own designs in “Can I Leave You?,” an exhibition at Providence’s RISD Museum.

For “Refashioning,” the four started with a simple question: “What is Japan Society?” CFGNY was interested in the organization’s founding in 1907 by U.S. businessmen who wanted to increase trade connections with Japan and, by proxy, with China — essentially, how an American organization was defining Japanese culture and identity for an American audience. While the early days of the society concerned itself largely with elite luncheons and society dinners, after the Second World War, the organization became a major booster of contemporary Japanese art and design in the U.S. The collective draws upon this legacy by re-creating the scene of fancy dinner parties with the commonplace materials of its own practice — instead of the more luxe finishes the society prefers — thus highlighting the highly manufactured aesthetic Japan Society uses to define Japan. One of the first things visitors may notice at the entrance to “Refashioning” sums up CFGNY’s project most succinctly: a looming wall of two-by-fours and plastic sheets, a makeshift assemblage that speaks to the constant process of deconstruction and reconstruction that animates the collective.

So c(fg) iet (n)y (2022).

Photo: Kirsten Kilponen/Kirsten Kilponen

A large flat screen displaying what appear to be fleshy innards intercut with Japan Society ephemera acts as a sort of primer to the Japan Society exhibition. The “innards,” in fact, are the interiors of CFGNY’s own sculptures, filmed with a borescope to create an effect at once intimate and alien. “It looks like the inside of a body,” notes Chew. At nearly 12 minutes, the video’s voice-over explains elements of the history of Japan Society that might otherwise go unnoticed or unconsidered in the sleek rooms.

From left: 119 W. 14th St. (2022). Photo: Kirsten Kilponen, Courtesy of CFGNYPhoto: Kirsten Kilponen, Courtesy of CFGNY/CFGNY

From top: 119 W. 14th St. (2022). Photo: Kirsten Kilponen, Courtesy of CFGNYPhoto: Kirsten Kilponen, Courtesy of CFGNY/CFGNY

This neo-Gothic gallery window is one of several fragments inlaid into the two-by-four-and-plastic sheaths the collective placed in the gallery. CFGNY was struck by the “New York American” appearance of the architecture from the society’s early headquarters. “When placed in this sort of ‘Japanese’ architecture, there’s this dissonance that’s really at the core of the history of this place,” says Chew.

The CFGNY members were also inspired by diasporic travelers’ frequent use of cardboard boxes for sending American goods throughout Southeast Asia, and they find themselves generally drawn to refuse and castaway materials.

Izu adds that using a commonplace product presents “a very different construction of the idea of Asianness” than the institution’s imported cypress-wood ceiling and slate indoor reflecting pool. “Cardboard is this universal shipping material that moves alongside people, and material and people become this same kind of commodity as they move around the world,” they say. “The material conveys this vague Asian sensibility of a cheap export or foreignness in the same way that Japan Society wants to distill this idea of Japaneseness through its architecture and through its society programming.” As Chew says, CFGNY and Japan Society’s aesthetics come from “very different class structures.”

Consolidated in Relation, Slate (1 Bottle, 1 Blouse, 7 Vases) (2022).

Photo: Sammie Anselmo, Courtesy of CFGNY

Green and white and peach, at first this vessel appears to be abstract and geometric — made of rectilinear forms disrupted by sluices and twists. “It’s only on closer inspection you can see all these impressions that are like ghosts,” says Kilponen: The foot-and-a-half-tall vase is not the result of formalist handiwork but rather from binding together ordinary consumer items like bottles and blouses as the basis of a plaster mold, which is then used to create the finished porcelain product.

“An important fact about these particular ceramics is that some of them could not have been done with one person alone because of the sheer size and sheer weight of these plaster molds that we created for them,” explains Kilponen. The CFGNY members further mixed up authorship by glazing one another’s sculptures.

“Subtitled” (2017).

Photo: Naho Kubota

While “Refashioning” opens with more recently designed clothes by CFGNY displayed on cardboard mannequins, this 2017 silk and cotton garment is placed over a cardboard chair modeled after those in the Astor hotel’s banquet room, where the society once held its luncheons.

CFGNY first experimented with draping in its 2019–20 show at the RISD Museum, where it placed custom garments over the furniture and floors, as if strewn by someone changing quickly. And while other garments were made for this exhibition or debuted at a runway show — Fashion Max 2 — in January, this dresslike piece comes from “Subtitled,” CFGNY’s first collection. Chew says that at the time, they “were interested in how we could distort straight lines and strict rigidities in the layering of different patterns. A grid pattern on top of a plaid on top of a gingham created a cacophony of noise that somehow broke through barriers to create something new and beautiful.”

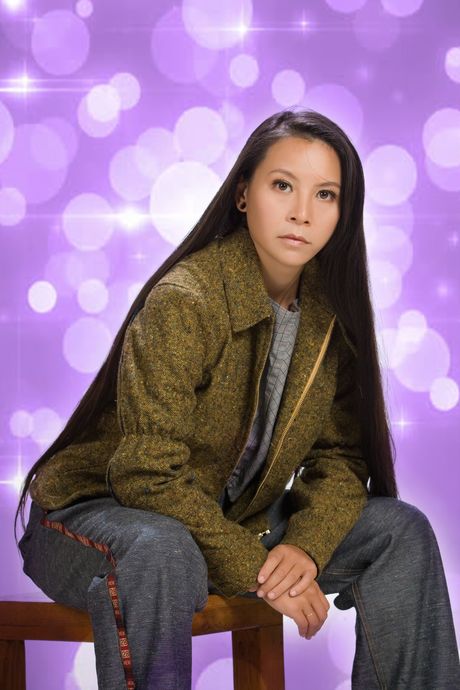

From left: Detail from Studio Phong photo wall (2017). Photo: Courtesy of CFGNYDetail from Studio Phong photo wall (2017). Photo: Courtesy of CFGNY

From top: Detail from Studio Phong photo wall (2017). Photo: Courtesy of CFGNYDetail from Studio Phong photo wall (2017). Photo: Courtesy of CFGNY

CFGNY has built relationships over the years with tailors largely patronized by westerners in Ho Chi Minh City. The results have focused on “signifiers of ‘general Asianness’ like mandarin collars or rice-bag jackets that almost appear as if they are made of pleather. For this photo series, CFGNY gave a Vietnamese photo studio total freedom to art-direct and edit the photos of its garments on local models. The results are sparkly glamour shots, which Nguyen notes are “a really traditional way of creating images within Vietnamese culture,” stylized like the pictures his parents have had taken of themselves.