Peggy Nolan had just turned 40, when, on a whim, her father gave her a Nikon camera that had been left unclaimed in his pawnshop in Miami. Back then, in the early 1980s, she was raising seven children – four boys and three girls, ranging in age from two to 17 – in a government-subsidised house in Naranja, a suburban neighbourhood near Miami. Untutored but curious, she began to photograph her immediate environment and soon realised that she had found her own, singular way of seeing the world around her.

“At first, I really didn’t know what I was doing,” she says, “but I remember shooting a picture through the leaves of the trees in front of the house and suddenly knowing somehow that this was how I should do it, this was how I should look. It was innate.”

Since that transportive moment, Nolan, who is now 79, has taken thousands of photographs of her family, storing the prints in sealed polythene bags to protect them in the event of a hurricane hitting the house. When she finally got around to doing an edit recently, it was her eldest son, Abner, who suggested that she show them to Paul Schiek, who he had taught at school and now runs a photography book publishing company in San Francisco. Schiek was suitably impressed, and in March, TBW Books will publish Juggling Is Easy, a monograph that highlights Nolan’s late-flowering talent. “My whole goal, my dream, was to have my work in books,” she says, excitedly. “I taught as an adjunct professor for years and I would compulsively buy photobooks to show to my students. It’s how I absorb photography.”

Even over a transatlantic phone line, Nolan has the energy of a forcefield, her thoughts tumbling out in sentences that flit from one subject to another. On the page, her images, too, possess a palpable physical dynamic that will be all too familiar to anyone raising – or raised in – a large family. In stark monochrome, she captures the constantly shifting drama of domesticity in moments of intimacy and abandon, reverie and wild recklessness.

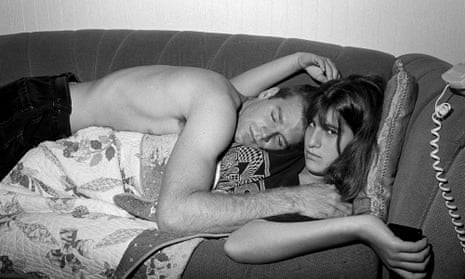

In one spread, a visceral image of a young cyclist, suspended in a midair spin high above a gaggle of teenage youths, is placed next to a photo of a young couple snogging in an eerily empty cinema. In another dramatic juxtaposition, a tiny figure jumps off a high wooden bridge into a river next to a portrait of young man lying languorously on a white wall like a fashion model. All teenage life is here, from the casually risk-taking to the artfully self-conscious.

In stark contrast, the interior domestic scenes are invariably cluttered and chaotic: unwashed plates and dishes soak in a basin next to where one of her daughters rinses her hair under a flowing tap; a child’s legs protrude from beneath a duvet in a bedroom filled with teenage detritus, including a bicycle, hi-fi speakers, a pet’s cage perched on a stool, and a sprawl of discarded socks, underwear and denims. In another almost posed image, a son in boxer shorts languishes on a vast tangle of newly laundered clothes. As her photography took over, Nolan tells me by way of explanation, she turned the laundry room into a darkroom. “It was breathtakingly scary to take a step outside what I knew,” she says. “But when I did, I became obsessed with this thing that was not all to do with family. There was a freedom to it.”

Over the years, her camera has also traced the passing presence of her children’s best friends, boyfriends, girlfriends and neighbours. She was there, too, lurking on the edge of the action when her kids went to the skatepark or the beach or, as they grew older and wilder, to punk rock gigs, pool halls and dive bars. And she was there, up close but almost invisible, when they chatted on the phone, made out, sulked or shared clandestine beers, cigarettes and gossip.

“There were definitely times when they had the sense that I was objectifying them,” she says. “And, in a way, they did become objects because, when I photograph, I’m not thinking about the people, I’m only thinking about the edges.” Did they get used to the camera in the end? “Well, after a time, you become invisible, but also as they grow up, they begin to have a different body language. They learn how to behave in front of the camera, to put masks on. They become much more self-conscious.”

Nolan grew up in Albany, upstate New York, a city brilliantly brought to life by the local-born novelist William Kennedy. In the 1960s, she studied creative writing at Syracuse University, where one of her classmates was the young Lou Reed, who a few years later would form the Velvet Underground. They were both tutored by the mercurial poet and novelist Delmore Schwartz. “Lou worshipped Delmore,” she says, “who was very troubled and, to me, made very little sense. He would stand up there and tell us about how his cat talked to him, and then we’d go drinking.” She worked as Schwartz’s housekeeper before his deteriorating mental health led to a stay in a nearby sanatorium. He was found dead in an alleyway of a seedy hotel in Times Square in 1966 at the age of 52.

By then Nolan had graduated with a degree in English and an ambition to become a writer but, as she puts it: “My chauvinistic marriage just killed it and I started popping out all these children.” That marriage lasted, on and off, for 20 years. She is reluctant to talk about her late husband, but told the writer Rebecca Bengal, who wrote the afterword to Juggling Is Easy: “I used all the energy that I used to use to make art.”

Nolan’s late embrace of photography was a liberation and a kind of salvation. In the late 1980s, she enrolled at Florida International University, graduating with a bachelor of fine arts in 1990 and a master’s in 2001, and has worked there in various capacities for nearly 25 years, teaching and using the darkroom. Early on, when times were hard, which was often, she stole rolls of film to feed her photography habit. “I was a notorious shoplifter,” she tells me, sounding almost nostalgic for her wilder days, and regaling me with the story of how she once got arrested in Mexico City and how that sobering experience “finally slowed me down”.

As a student, she took classes with the documentary film-maker Frederick Wiseman and studied a history of photography course under the curator and writer John Szarkowski, who had made his name as a visionary director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “I had a pretty tight relationship with Szarkowski,” she says, “but there weren’t too many women there. He had essentially established a boys’ club and he wasn’t too interested in my photography. Nevertheless, I learned a lot. In fact, some of his negative criticism made me feel better about what I was doing. I know I’m my own best editor, that’s for sure. Nobody knows what it’s like to be inside my head.” After we speak, she emails me a poem she wrote recently. It is entitled Ode to the Shark – the students’ nickname for Szarkowski – and includes the lines: “And I learned something / So painful: / That I was ordinary / And so were my eyes…” She is anything but.

When I ask who her early influences were, she responds immediately and with characteristic candour. “None of the big guys, that’s for sure. When I started out, it was Imogen Cunningham. She left her family for photography and that was shocking to me. I don’t imitate, but she gave me some kind of acknowledgment that I should do this. Also, I look at Diane Arbus’s pictures over and over because they have such presence.”

Considering Nolan’s work in all its dynamic and grittily honest depiction of working-class domesticity, it is evident that she was not the strictest of parents. There are pictures of the kids crashed out on mattresses, playing pool in dive bars, partying and snogging. In one, a boy peruses a Playboy centrefold. In another, a girl – a friend of the family – walks topless across the yard in a snowstorm. “No, I was not strict,” she says, laughing. “But my kids never got wild. I remember telling each of my daughters at a certain age: ‘From this moment on, your body belongs to you but there are consequences to that.’ But, you know, they all turned out pretty good – they had a self-esteem that was proper.”

When her children grew up and moved out, she had a moment of existential panic – “I just froze!” These days, she tells me matter of factly: “I’m living alone, single, doing my thing. I’m almost 80 years old and I don’t know how long I have left or what is going to happen. I have so many photographs, I could probably spend many years looking backwards, but I still photograph like crazy.”

Given how good her work is, I say, she had better get used to the attention that will inevitably come her way. “It’s very strange already,” she says, sounding uncertain for the first time in our conversation, “and, to be honest, I’m not that comfortable with it. From what I’ve seen, you have to be ruthless to be an artist, and I’m not ruthless. There’s a big part of me that’s still that person walking around in her pyjamas in the house.”