‘The most important painting of the 21st Century’

(Image credit: Amy Sherald/ Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth/ photo by Joseph Hyde)

Her painting of the late Breonna Taylor was hailed as groundbreaking, and artist Amy Sherald has blazed a trail with her portraits depicting black America. She talks to Precious Adesina about history, storytelling and the possibility of a new art canon.

I

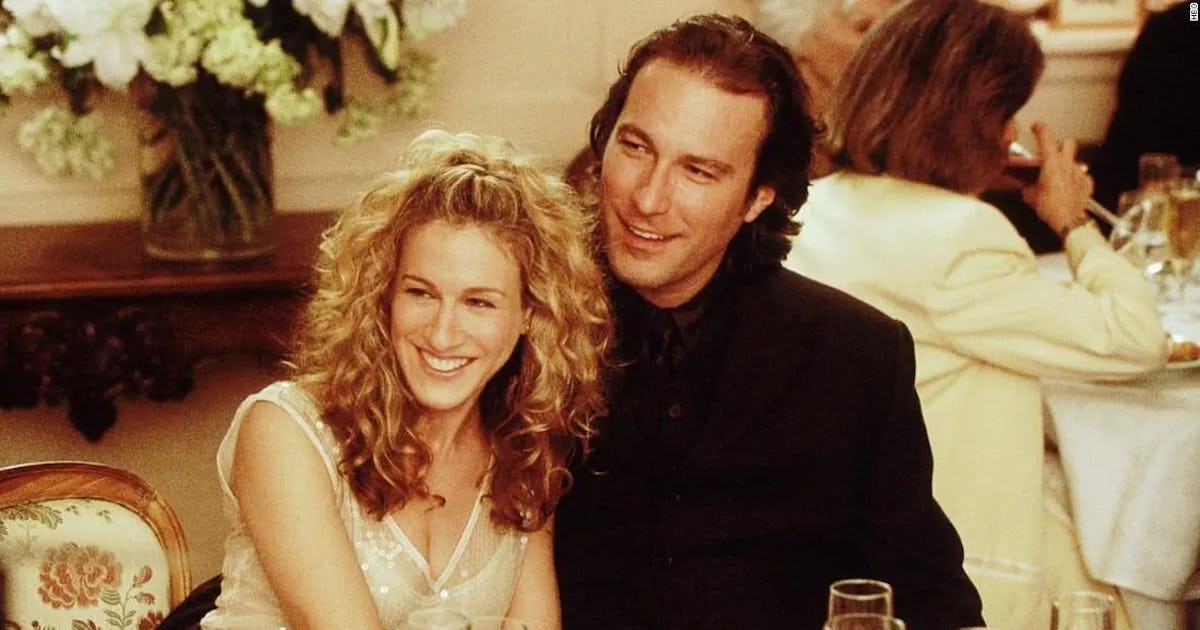

In 2018, the Georgia-born artist Amy Sherald was chosen to paint Michelle Obama for The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington. The portrait sees the former first lady portrayed in Sherald’s signature style: a grey skin tone, a simple backdrop (in this case a plain blue one) and a fashionable outfit that exemplifies the sitter’s character. The US fashion designer Michelle Smith created the high-neck maxi dress that Obama wears for the painting, with an abstract print that echoes Piet Mondrian’s geometric paintings. Discussing her Smithsonian piece in a recent interview, Sherald called Obama an icon. “She represents for me and a lot of women what 21st-Century womanhood looks like,” she says. The painting catapulted the artist into a new realm.

More like this:

– The woman written out of history

– The artist who skewers white privilege

– The artist who likes to blow things up

While the 49-year-old is often seen as an overnight success, in actuality, her star status has come from decades of perfecting her craft. “People think it’s this meteoric rise, but in fact, she’s been working for 20 plus years,” says US art historian Jenni Sorkin, who has written an essay on the artist for the catalogue of Sherald’s first European show – at Hauser & Wirth in London titled Amy Sherald: The World We Make.

Sherald was commissioned by the Whitehouse to create the official portrait of then First Lady Michelle Obama (Credit: Courtesy of the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery)

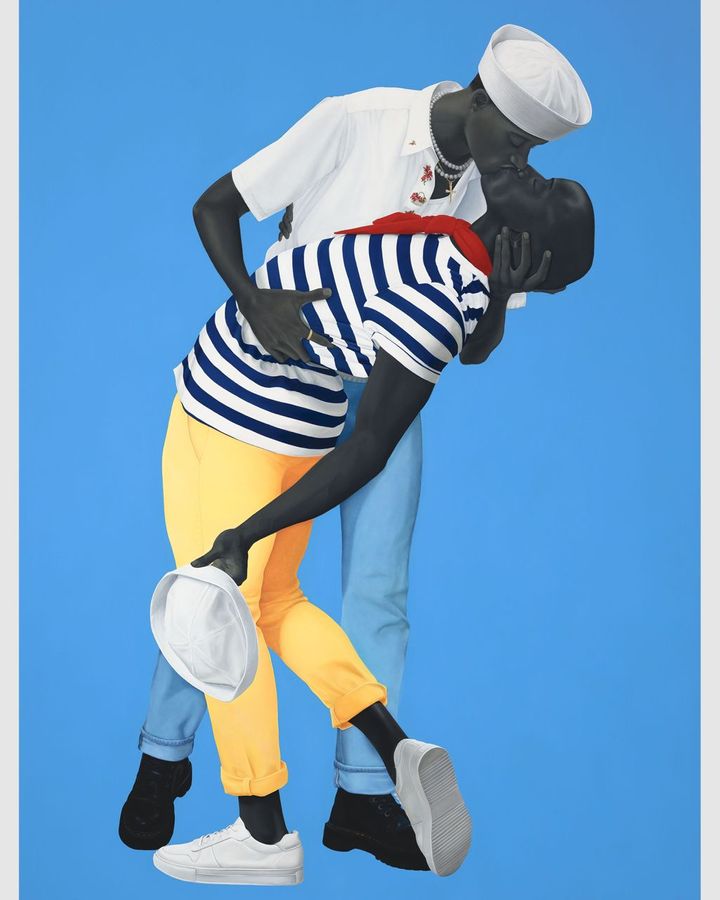

Sorkin notes that Sherald is also known for her posthumous portrait of 26-year-old Breonna Taylor, created in 2020 for the cover of the September issue of Vanity Fair, and which Forbes called “the most important painting of the 21st Century”. Taylor was killed in her home in Kentucky by police officers, a tragic story that partially fuelled the worldwide Black Lives Matter protests that same year. “Sherald gained extreme prominence with these two major commissions, but the first was the Michelle Obama one,” Sorkin adds. “Being chosen for that put her on a national stage in a different way than she might have been otherwise.”

Sherald plays with photography and portraiture, a technique that has been a core part of her practice. Instead of painting from life, the now New York-based artist photographs her subjects, and depicts them from the imagery she collates. “When you’re painting from a photograph, there is a level of autonomy,” says Sorkin. Creating paintings in this way often allows Sherald to easily make minute changes to enhance the portrayal of her subjects. “The shadowing, profile and accessories can be fixed by the painter. Often Amy photographs the model, and swaps clothing choices out later.”

Sherald herself is very stylishly dressed. Talking at London’s Hauser & Wirth gallery in early October, she is wearing a white turtleneck, long khaki skirt, and thick black boots with her hair slicked back in a low bun. The use of trendy clothes to dress her subjects is integral to her practice. Still, despite this and her interest in photography, Sherald doesn’t associate her work with fashion photography. “Fashion photography is a combination of product, portrait and even fine art photography, as a genre where art and commerce meet,” she tells BBC Culture via email. “I am interested in creating images within and beyond those contextual structures to anchor them in a timeless historical lineage.”

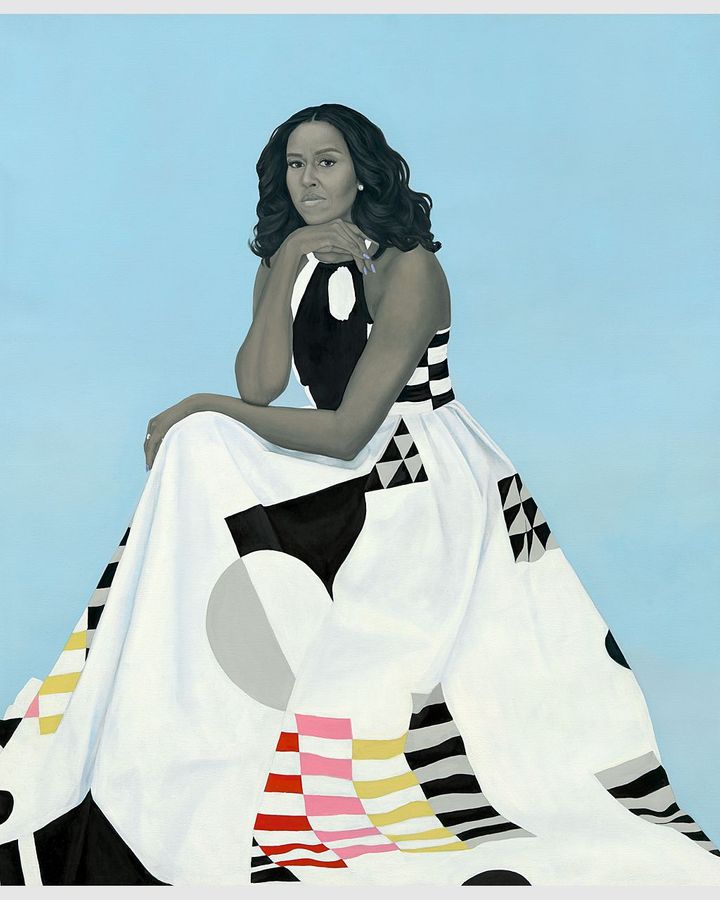

Sherald’s For Love and Country, 2022, recreates the famous 1945 photograph V-J Day in Times Square (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth/ photo by Joseph Hyde)

Instead, Sherald uses her understanding of the digital medium to create works that naturally embody and uplift black people. In the painting For Love, and for Country (2022) in The World We Make exhibition, Sherald uses the positioning and attire of the two black men in her painting to recreate the famous photograph by Alfred Eisenstaedt, first published in Life magazine in 1945. The image shows a US sailor embracing and kissing a woman on Victory over Japan Day (“V-J Day”) in New York City’s Times Square on 14 August, 1945. In Sherald’s painting, two black men dressed as sailors also passionately kiss in the same way. “I feel like right now was the perfect time to make this more visible,” she says of queer relationships. According to CNN, LGBTQ+ rights are being threatened by a record number of anti-LGBTQ+ bills across the US, with state lawmakers introducing at least 162 bills targeting LGBTQ+ Americans this year. Sherald also adds that images like Eistenstaedt’s are what we immediately associate with art history. “My work offers another narrative of what that canon might look like, and how it can take shape through new, expansive storytelling.”

Shades of grey

A crucial part of Sherald’s work is her use of grisaille, a technique in which an image is created entirely in shades of grey. “When I first started painting the black figure, I recognised that we are a political statement in and of ourselves,” she says. “I didn’t want the work to be marginalised and for the conversation around it to solely focus on identity or politics.” Sherald uses grisaille in place of skin tone, which she says has a “universal quality” that allows her to “subversively comment on race”.

“It also calls on the influence of photography, specifically daguerreotypes which, through the work of Frederick Douglass, allowed [black people] to become authors of [their] own narratives.” Douglass was a US abolitionist who wrote about the power of photography to provide black people with representation free from racist stereotypes, and encouraged people to take images of themselves.

Sherald’s posthumous portrait of Breonna Taylor, 2020, depicts the subject in a future she was denied (Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth/ photo by Joseph Hyde)

With Sherald’s expansive and consistent oeuvre in mind, it is no surprise that she was chosen to portray both Michelle Obama and Breonna Taylor in recent years. Historically, White House portraiture has been very white, both behind and in front of the canvas or camera. “The Obamas were the first black president and first lady to inhabit the White House, and they themselves were under a magnifying glass for the entirety of the administration,” says Sorkin, explaining that the Obama family were scrutinised more intensely than their white counterparts, and subject to extreme racism. “Selecting a black female portrait painter to represent Michelle Obama, a black woman in the White House, is a huge boon in terms of showcasing representation that previously didn’t exist.”

In contrast, Sherald’s painting of Taylor was the first portrait she had painted after a subject’s death. “When Ta-Nehisi Coates came to me with the invitation, I had never considered painting someone posthumously. My practice is based on finding live models,” she says. Coates is a US journalist and author who was guest editing Vanity Fair’s September issue at the time. “I began to do research looking for any images I could find that had not already been used.” Sherald portrayed Taylor in a long green dress with high slits against a similarly-coloured background. “When I asked her mom to describe Breonna, she sweetly said that she was a diva in the best sense of the word. She loved getting dressed up. She was always put together,” Sherald explains. “I painted her how I thought her family would want to remember her.”

According to Allison Glenn, who curated the 2021 exhibition commemorating Taylor at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky, what makes Sherald’s painting stand out is its symbolism. “She could be anybody. She could be your sister, your cousin, your friend, your aunt, your mother, your granddaughter, your daughter, your wife,” Glenn tells BBC Culture, adding that Sherald appears to have depicted Taylor in the future. “She included the engagement ring that her fiancé was going to give to her, and imagined how she might want to be represented.”

The artist Amy Sherald pictured at the opening of her show, The World We Make, at Hauser & Wirth, London (Credit: Joseph Hyde)

When Sherald looks back at her older works, she feels a sense of nostalgia. “Growing a practice is about the journey, and there are some sweet moments in some paintings that remind me of how far I’ve come,” the artist says. “It’s like looking back at a diary.” But her new work is beginning to reflect some more personal touches. In her show at Hauser & Wirth, Sherald revealed the first painting she has made of a family member, titled He was Meant for All Things to Meet (2022). It shows her lacrosse-playing nephew (her partner’s twin’s son) in a lime-green jumper and denim trousers in front of a lighter green background. “My partner and his brothers grew up in Bedstuy and Flatbush in the 80s,” Sherald says, explaining that they were raised in a difficult setting. “Families living in urban environments [at the time] had to be concerned with public safety and the crack cocaine epidemic.”

Now Sherald’s three nephews attend an elite private school, and the one depicted in her painting is the school’s first black student-body president. “When I look at my nephew, I see a young man with a big future. Hence the title, He was Meant for All Things to Meet.” Glenn suggests Sherald will continue to break new ground. “I’ve seen Amy’s practice growing in really strong, subtle ways over the years. But she could completely surprise us. The painting of the embrace of the two men was such a surprise.”

Amy Sherald: The World We Make is at Hauser & Wirth, London, until 23 December

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.