Melvin Sokolsky, a photographer whose fantastical and once in a while surreal work introduced an experimental electrical power to Harper’s Bazaar and style imagery in the 1960s, died on August 29 in Beverly Hills, California. He was 88 a long time outdated.

Sokolsky’s death was announced on Instagram by David Fahey, the co-founder of his gallery, Fahey/Klein, in Los Angeles. A cause was not offered.

In an period of cultural upheaval, Sokolsky sought to unmoor style photography from its much more classicist—and classist—roots. His tales ended up bold, otherworldly, and normally technically and logistically intricate to pull off, all in the times right before digital know-how would simplify the process of taking and manipulating photos.

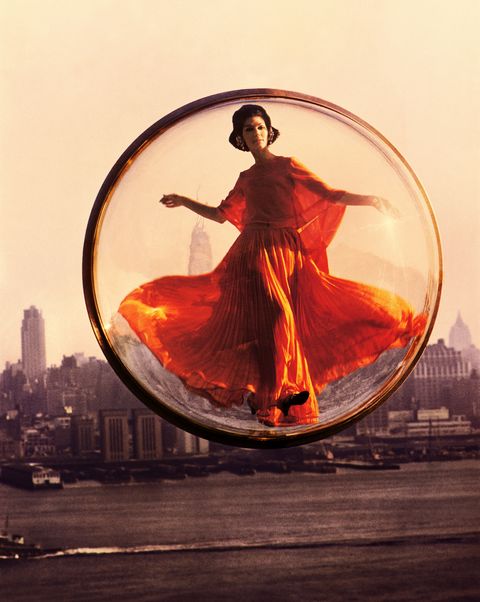

Maybe the most well known of them was his March 1963 “bubble” collection for Bazaar, which highlighted product Simone D’Aillencourt floating in a space-age-y translucent orb that begins its journey in New York before settling previously mentioned the Seine in Paris. The session would develop into Sokolsky’s calling card at a moment when a variety of youth subcultures and social movements have been hard the previous-culture swirl and European perspectives that experienced long dominated large manner. Bazaar by itself was also in a time period of transition, as many of the legendary imaginative forces of the magazine’s vaunted postwar golden age—editor in chief Carmel Snow trend editor Diana Vreeland art director Alexey Brodovitch and shortly photographer Richard Avedon—had retired or were being in the system of departing.

Born in New York in 1933 and elevated on the Lessen East Facet, Sokolsky was self-taught and skilled as a photographer. He was generally interested in art as a child and experimented with his father’s digital camera. But from a youthful age, Sokolsky was driven by the notion that he would want to function to assist support his family members soon after his father was identified with various sclerosis when Sokolsky was nevertheless in high school.

Sokolsky’s huge crack would come in 1959, when Brodovitch’s successor at Bazaar, Henry Wolf, spotted an ad in the journal that Sokolsky had shot. Wolf identified as Sokolsky and presented him an assignment, which would incorporate an try at a cover image. Sokolsky was anxious, but Vreeland’s assistant at the time, Ali MacGraw—who, following showing in Like Story (1970) and with her future husband Steve McQueen in The Getaway (1972), would go on to become just one of the most significant motion picture stars of the 1970s—alerted him to a hat that Vreeland loved, which he built sure to shoot. Sokolsky didn’t get the go over, but he before long grew to become a standard contributor to Bazaar.

Nonetheless, the bubble sequence came at an inauspicious time for both Sokolsky and the magazine. Wolf experienced still left in 1961, with Vreeland decamping the adhering to calendar year for Vogue, wherever she would soon be named editor in chief. In December 1962, Sokolsky was requested to shoot a story on the Paris collections, but Wolf’s substitution, Marvin Israel, and Bazaar’s editor in main, Nancy White, both equally experienced reservations about the notion he had proposed: he wished to photograph a design in a big bubble hovering higher than the city.

Sokolsky, although, was established on the strategy, inspired in element by the Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch’s 15th-century triptych The Backyard garden of Earthly Delights, which depicted the tale of generation and incorporated very small figures and animals in floating clear bubble-like spheres. Sokolsky remembered remaining fascinated by that portray as a teen, imagining himself within a person of them, effervescently building his way around the city. He also recalled seeing a division keep window display where the footwear and purses ended up organized in clear, spherical plastic containers.

When White and Israel blanched at the feasibility of the task, Sokolsky agreed to do some examination shots. He had two big Plexiglass hemispheres fabricated and connected them with a metal ring that spanned the circumference of the bubble and was hooked up to a skinny steel cable. He set up camp in Weehawken, on the New Jersey aspect of the Hudson River, and rented a crane, which he then made use of to hoist the bubble into the air with D’Aillencourt inside, photographing her versus the backdrop of the Manhattan skyline.

In late January 1963, Sokolsky established off for Paris with D’Aillencourt and MacGraw, who had left Bazaar to do the job for him in the hybrid position of assistant, producer, and fixer, together for the experience. “Melvin questioned me if I could dredge up my high-school French in get to interface with the Paris law enforcement for authorization day and night to established up our crane,” MacGraw recalled of the shoot final 12 months. “They were being really amused and allowed us to shoot nearly everywhere.”

The images of an elegantly dressed D’Aillencourt suspended in midair in a plastic bubble felt eerily futuristic—and entirely different from the established vernacular of fashion photography at the time. The women in his pictures weren’t ethereal creatures who populated salons, lush gardens, and environments that immediately read as privileged. They were individuals with agency, trying to navigate a changing world. As he later recounted, the character D’Aillencourt embodied in the bubble series wasn’t, in his mind, trapped in the device but in command of it. “I secretly saw it as a Sokolsky aircraft that could fly anywhere on an engine built into of the ring,” he said in 2019. “It was not a girl captured in a bubble. It was a woman at the helm of her spaceship.”

Sokolsky’s bubble series became the first blockbuster fashion story for Bazaar in the post-Vreeland period. It also marked the beginning of a prolific creative run for Sokolsky, an inveterate storyteller whose images evoked multidimensional characters and fable-esque narratives but were often set in realistic—and in some cases, hyper-real—environments.

For a shoot that appeared in the November 1963 issue, Sokolsky once again looked to art for inspiration. Drawing upon the surreal scale in René Magritte’s 1952 painting Personal Values, which depicted the contents of a bedroom—a glass, a comb, a matchstick, and a brush—rendered enormous and propped up on the furnishings, he shot a feature that involved models climbing and leaping off a gargantuan chairs and other furniture. “My mother’s old kitchen chair was stored in the studio prop room—a simple kitchen chair that I grew up sitting on,” he told Bazaar in 2021. “I asked the carpenter to scale it up to 10 feet.”

In early 1965, Sokolsky returned to Paris for another story, this one with model Dorothy McGowan, who appeared to be flying (sans bubble) around the city McGowan was, in fact, suspended by a corset-harness contraption that Sokolsky once again devised himself. “Watching Dorothy dangle five stories above the street from a thin cable anchored to a steeply angled roof was unsettling,” Sokolsky said. “To this day, I can picture her flying above the city, bouncing at the end of the cable, actually enjoying the experience.”

By the early 1970s, Sokolsky had moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career in film. He began working as a commercial director and cinematographer, which would become his primary focus over the next several decades. But a resurgence of interest in his photography in the late 1990s prompted a return to creating still imagery, which he continued to experiment with and push the boundaries of in recent years. For Bazaar’s December 2014/January 2015 issue, he even revived the bubble for a cover story on Jennifer Aniston.

Sokolsky saw appreciation for his work ebb and evolve, but he remained enthralled with it all. Last year, he pointed to a color outtake from the big-chair story, which ran entirely in black and white. In the image, the model Iris Bianchi is seen leaning off the giant chair in a red print coat, as if she’s about to either tumble forward or leap out of her seat. That outtake, Sokolsky said—more than any of the pictures that actually appeared in the magazine—was the one galleries and museums always requested for exhibitions. “The art department thought the image was so weird,” he told Bazaar. “At the time most choices for publication were upper-class gestures by the models,” he said. “But times and tastes have changed. The out becomes the choice, setting a new standard.”

Sokolsky is survived by his son, Bing Sokolsky, and daughter-in-law, Yuki Sokolsky. He was predeceased by his wife and longtime collaborator, Button Sokolsky.